- Dettagli

- Categoria: Women views on news

- Pubblicato: 26 Febbraio 2014

Works by women artists at the two London Tates tackle political and industrial issues.

Works by women artists at the two London Tates tackle political and industrial issues.

A ‘spotlight display’ in the TATE Britain on Millbank, called Women and Work, looks at the industrial issues of the 1970s from an overtly feminist perspective.

Between 1973 and 1975 artists Margaret Harrison (born 1940), Kay Hunt (1933–2001) and Mary Kelly (born 1941) conducted a detailed study of women who worked in a metal box factory in Bermondsey.

Their investigation was timed to coincide with the implementation of the Equal Pay Act, which had been passed in 1970.

They collected a vast amount of data through interviews, archival research and observation.

‘Women and Work’ was one of the earliest projects to tackle political and industrial issues from an overtly feminist perspective.

The use of sociological method as a conceptual strategy is emphasised by the minimalist look of the work itself, where black and white photographs and films sit alongside simple typewritten texts and photocopied charts and documents.

Punch cards and rates of pay record the gap in wages between men and women, and films of life in the factory show women confined to repetitive, stationary and low-skilled tasks while men perform more physical and supervisory roles.

‘Women and Work’ was one of the earliest projects to tackle political and industrial issues from an overtly feminist perspective.

Objective and subjective points of view coexist, and the points of contact between the personal and the political, the public and the private are themes that run throughout.

The named portraits of women employees put human faces to the facts and figures and invite the viewer to engage with the issues on more personal terms.

On Level 4: The Schmidheiny Gallery at the TATE Modern, artwork by four women and made over four decades, subverts materials traditionally associated with feminine craft and the domestic sphere to address gender division and political themes.

Markedly different in tone and technique, these works share an interest in textile production, a heavily gendered activity which has played a huge part in the construction of women’s identities as housekeepers, family carers, makers and workers.

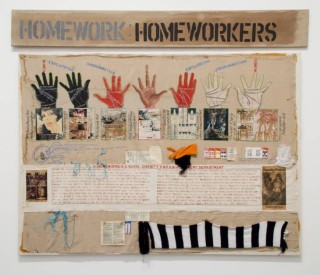

Margaret Harrison made ‘Homeworkers‘ in 1977 to denounce the working conditions of women in Britain, who were often treated as second-rate labour and encouraged to perform low-pay manufacturing jobs from home.

At once a political banner, a symbolic painting and a social study, it represents the everyday life of a working woman alongside advertisements for make-up and data on the history of workers’ movements.

Rosemarie Trockel’s knitted works resist associations with ideas of female craft by becoming standardised industrial products.

Her machine-made patterned fabrics, mounted on stretchers to resemble geometric canvases, turn symbols of power into decoration, and geometric motifs into subliminal propaganda.

In Annette Messager’s The Pikes, soft figures and little drawings mounted on sticks initially suggest a parade of makeshift toys. On closer inspection, however, they reveal a darker nature, with severed heads and limbs alongside images of traumatic events from history and the mass media.

Tracey Emin’s quilts create a dissonance between their explicit content – in this case a rebuke of Margaret Thatcher’s involvement in the Falklands war – and the homely values associated with quilting.

Women at Work, a spotlight display in the Tate Britain, runs until 23 March.

Leggi tutto... http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/WomensViewsOnNews/~3/owFDNzPtO_Q/